Choosing a Liberating Hope

As I think back on this year, one of the things that comes to mind is how many times I’ve heard people say “I’m finding it hard to stay hopeful.” Hearing this so much has led me to give some considerable thought to what keeps me hopeful.

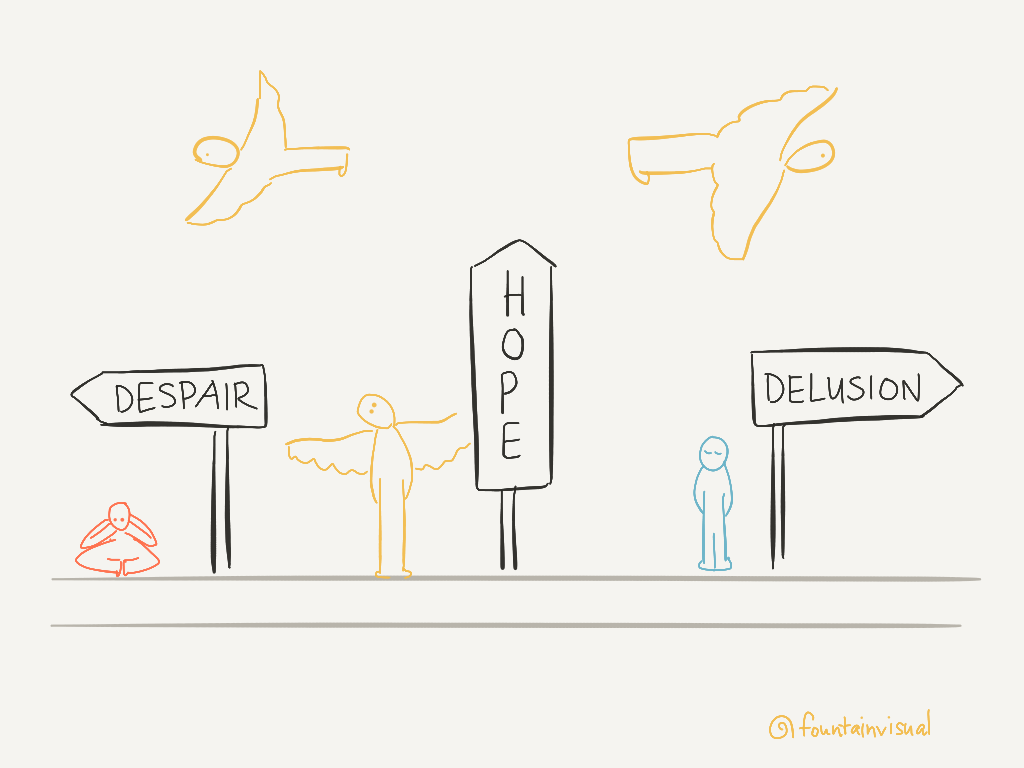

I wonder if I don’t find it to be as hard as it seems to be for others because frankly I am so familiar with despair that I long ago accepted that cultivating an attitude of hope is my only healthy choice. I feel like when I hear others talk about hope, they think of it as a result of external circumstance, like the news or something is supposed to make them hopeful or is the reason they are not. However, I think it’s strictly an internal attitude and experience.

I consider this to be good news, for it’s available to us whenever we choose, regardless of circumstance. Like most seemingly-fragile things - relationships, dreams, health, success - hope is something we yearn to acquire, develop, protect, preserve and cherish. Unlike these other ephemeral gifts, however, hope is something we always have a choice about.

It is what Abraham Lincoln referred to when he wisely said “Most folks are as happy as they make up their minds to be.” I trust this wisdom all the more because he endured poverty, bankruptcy, failure in eight elections, civil war, the untimely loss of three of his four children, and, understandably, chronic mental health issues.

I think my own commitment to choosing hope stems from my belief that hope is not only essential for our survival, it is also a prerequisite for making any change happen. In the ever-gifted words of Martin Luther King Jr.: “Revolution, though born of despair, cannot long be sustained by despair . . . The only healthy answer lies in one’s honest recognition of disappointment even as he still clings to hope, one’s acceptance of finite disappointment even while clinging to infinite hope.”

What King touches on here is critical: hope isn’t about ignorance. In my experience, if we don’t first choose to be honest about what is, another weighty task in and of itself, we are liable to pay the high costs of naivety, foolhardiness, or self-destructive fantasy.

In numerous situations in my own life I have at times chosen to “stay hopeful” as a way of resisting reality, of avoiding hard choices and resisting wise changes. I kept telling myself “it will get better in time” as a way of ignoring my responsibility to make it so and of denying uncomfortable realities.

This is the sort of illusion that the Buddhist teacher Pema Chödrön advises we drop. “As long as we’re addicted to hope, we continue to suffer a lot . . . We hold onto hope and it robs us of the present moment . . . Abandoning hope is an affirmation, the beginning of the beginning . . . Giving up hope is encouragement to stick with yourself, not to run away, to return to the bare bones, no matter whats going on. If we totally experience hopelessness, giving up all hope of alternatives to the present moment, we can have a joyful relationship with our lives, an honest, direct relationship that no longer ignores the reality of impermanence and death.”

To be clear, this does not mean we allow ourselves to sink into complacency and passivity. The tensions that we become awake to when we cease running from reality require us to take action. Hope is what we need to rise to the occasion. It is an invitation to become the change we seek.

“Men often become what they believe themselves to be. If I believe I cannot do something, it makes me incapable of doing it. But when I believe I can, then I acquire the ability to do it even if I didn’t have it in the beginning.” This is one of my favorite quotes from Mahatma Gandhi. It reminds me that my ability to cultivate hope may be one of the many blessed lessons I’ve received as someone committed to developing creatively.

When we start making something, anything, whether it be a thoughtful email, a stunning outfit, an exciting meal, a drawing, a song, a dance routine, we are bound to sense potential failure. Many people I think choose to play it safe by doing only what they know they won’t fail at; they give up on anything too risky, challenging, or new.

Some of us like testing our limits, going to the edge of what we know we are good at to discover what happens when we do indeed fail. Those of us who keep going when things go “wrong” understand that we have a choice just like everyone else. We simply choose to believe that even if we can’t at first, eventually we will. We know another failure is guaranteed, and yet we choose time and time again to keep moving into the unknown, to begin again and again and again, to do whatever is necessary for the unpredictable creative process to unfold.

Of course we are in no way immune from the societal plagues of fear, doubt, and despair. I was recently a part of a discussion among creatives about environmental ethics which concluded with the facilitator asking “So who’s hopeful?” My hand was one of three raised in a room of more than 20.

I was surprised to see this in a group that I know understands that on the other side of risk, of blundering, of grief, of ridicule we can find joy, fulfillment, grace, possibility, even if the results are entirely different from what we imagined or wanted them to be. We know from experience the power of hope.

Hope is hard to hold onto though. Yes, it’s fleeting, it’s fragile, it’s easily misunderstood or taken for granted, and it’s also unpopular. It is much more convenient to join the frustrated complainers, to focus on the tragic headlines, to succumb to our brains’ negativity bias, to allow ourselves to slip into resentment and self-pity.

This is why hope cannot ever be passive. It cannot be a mere sentiment we claim, it must be a verb, it must be evident in the actions that we regularly take. This is how it will be useful, sustained, and infectious.

One simple step toward choosing a liberating hope is to be intentional about where we put our focus and attention. Living in the information age and the attention economy makes this more challenging - and more critical. We may not be able to choose what the publishers create, what the broadcasters discuss, nor what the cacophony of commenters protest, but we can choose how much importance we give it, how we carry these conversations into our daily life, and what we choose to do with the new information it may present.

We can also seek out the good news, knowing that to counteract our brain’s innate negativity bias we’ll need about five positive messages to outweigh every one negative one. Here’s some good sources I’ve found:

Our own lives can also provide ample evidence of hope and progress if we endeavor to look for it: the kindness between strangers, the natural optimism of children, the enduring strength of elders, the brave actions of all types of leaders, the beauty of the natural world, the gifts of healing laughter and tears, the creative human spirit.

One of the most potent actions we can take to cultivate hope in our lives is simply to surround ourselves with loving people who are using their lives to be part of creating solutions. In turn, one of the greatest challenges we may face cultivating hope is rising above the influence of others we may be surrounded by who choose to focus on their anger and fear or who believe in nihilism.

It is impossible to choose hope if we think our lives and our actions don’t matter. In my opinion, this kind of thinking is plainly false. Through the course of human history, countless individuals have made a difference in their lives and in others, which is why we are no longer ruthless cannibals wandering across the plains. If we look at history from a more long-term, ecological viewpoint, again we are forced to recognize that collectively humans have had a more powerful impact that any species of life ever has. Of course we are important - each of us.

Knowing we matter can scare us, though. “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us,” writes Marianne Williamson.

It may be that this fear is the most challenging one for us to overcome as each of us strives to “cling to infinite hope” in a time in which our planet and species is facing an existential crisis. If we truly believe what Marianne Williamson writes, that “we are all meant to shine,” we are forced to accept an immense responsibility, not merely for the consequences of our own individual actions but also for the future of our collective humanity.

Again, the reason I trust the words of the aforementioned sages is that I know that they, like me, have known deep darkness. Like others before them, they allowed their despair to transform them into people whose lasting impact is unquestionable, and they have done so by cultivating hope, in themselves, in their communities, in the world.

Hope doesn’t protect us from moments of despair, but it does give us a way to press on in spite of it. It is a wisdom that tells us to keep going even when we can hardly sense what’s ahead, to show up when we want to run or hide, to choose to embrace the promises of life in the face of the certainties of death, to use both our individual and our collective strengths to evolve.

I would be remiss if I wrote an article about hope and didn’t supply the powerful words of Viktor Frankl, a man who survived a Nazi concentration camp to develop a psychotherapy emphasizing the pursuit of meaning: “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms - to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances . . . When we are longer able to change a situation we are challenged to change ourselves.”

Did you enjoy this article? Join my monthly email list or get content every week via my Patreon page.

You can also check out these related articles: